Ruins of housing believed to have been used by soldiers stationed at the garrison.

Alice Martins for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Alice Martins for NPR

Ruins of housing believed to have been used by soldiers stationed at the garrison.

Alice Martins for NPR

DIYARBAKIR PROVINCE, Turkey — As part of what was once ancient Mesopotamia, Turkey has long been fertile ground for archaeologists. It’s home to significant sites that even predate Mesopotamia — UNESCO World Heritage Sites such as Gobekli Tepe, a Neolithic settlement believed to be more than 10,000 years old with what may be the world’s oldest place of worship, and Catalhoyuk, a proto-city dating back some 9,000 years.

Now, more recent sites in the country’s southeast are yielding finds that archaeologists say may change modern understanding of this part of the world’s past, moving the footprint of pre-Roman activity in the area farther east than was previously believed.

Zerzevan Castle, the site of a Roman Empire military garrison, is providing what UNESCO calls “important information about the Roman soldiers, civilians’ daily lives and the battles.”

And then there’s the Mithras Temple. The Mithras religion — also known as the “Mithras cult” — is believed to have originated in ancient Persia, and the temple, discovered in 2017, is possibly the best-preserved such temple in the world, says UNESCO.

Yet to be excavated are huge, multistory structures that archaeologists have identified thanks to ground-penetrating radar scans. These remain below ground and are revealing layer upon layer of artifacts, some dating back well into pre-Roman history.

A local family visiting Zerzevan Castle archaeological site.

Alice Martins for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Alice Martins for NPR

A local family visiting Zerzevan Castle archaeological site.

Alice Martins for NPR

Archaeologist Aytac Coskun, seen at ruins of an ancient church, says excavations in the area may continue for another three decades.

Alice Martins for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Alice Martins for NPR

Archaeologist Aytac Coskun, seen at ruins of an ancient church, says excavations in the area may continue for another three decades.

Alice Martins for NPR

Sitting near an ancient church built on a hill high above the temple, archaeologist Aytac Coskun says the first time he saw the place, he knew he had to excavate.

“I first came to Diyarbakir in 2005,” says Coskun, “and when I saw this hill, I saw some pieces of artifacts, and I knew no excavation had been done before. So as soon as I saw it, I knew it had to be a dig because there must be something significant underneath.”

Underground residential areas may have sheltered 10,000 people in wartime

A tour of the site reveals some what he and his team have excavated in recent years — a sprawling rock altar, an underground church, a water canal stretching for at least several miles.

A member of the Zerzevan Castle excavation and restoration team looks into a microscope while studying a coin found at the archaeological site.

Alice Martins for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Alice Martins for NPR

A member of the Zerzevan Castle excavation and restoration team looks into a microscope while studying a coin found at the archaeological site.

Alice Martins for NPR

A bronze baptismal bucket found at the Zerzevan Castle site, currently on display at the Archaeology Museum of Diyarbakir.

Alice Martins for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Alice Martins for NPR

A bronze baptismal bucket found at the Zerzevan Castle site, currently on display at the Archaeology Museum of Diyarbakir.

Alice Martins for NPR

Coskun and his team have unearthed objects including a beautifully preserved and ornately decorated Roman-era bronze baptismal bucket and an Assyrian-era stamp, a kind of official seal carved into rock, that could date back some 3,000 years.

“The digging we’re doing inside the castle walls is 57,000 square meters [68,171 square yards],” he says. “It’s a huge area. And outside of it…is (something) like 10 million square meters [3.86 square miles].”

Coskun believes some 1,500 people, both military and civilian, lived here during times of peace. In wartime, he says, it’s likely that some 10,000 people from the surrounding area came here to seek shelter.

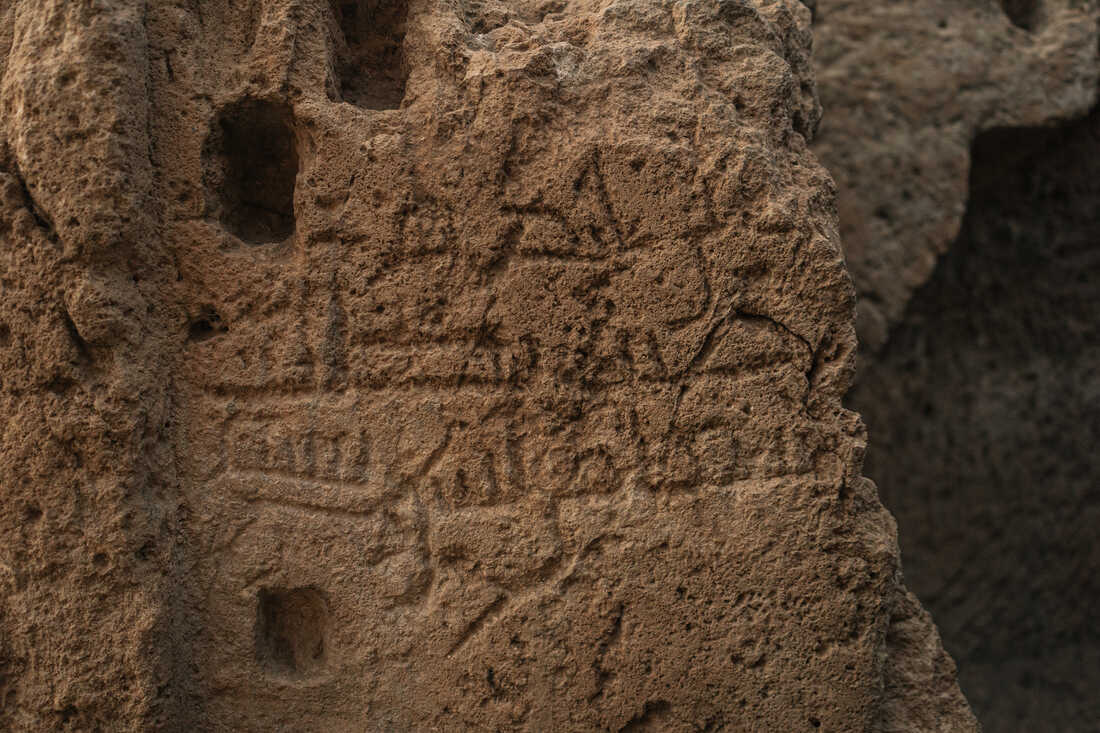

An inscription seen at the entrance of the Mithras temple which remains undeciphered.

Alice Martins for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Alice Martins for NPR

An inscription seen at the entrance of the Mithras temple which remains undeciphered.

Alice Martins for NPR

Ruins of the church seen from the south tower.

Alice Martins for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Alice Martins for NPR

Ruins of the church seen from the south tower.

Alice Martins for NPR

That, he says, may help explain the expansive underground living areas. So far, he says they’ve excavated six residential complexes inside the castle walls, and there are 99 more still below the surface.

That’s just one reason Coskun says this site has the potential to change modern understanding of this part of the world and its archaeological and architectural history.

“It’s totally open to new discoveries, that’s for sure,” he says. “We don’t know what else we’ll find. We’ve only dug around 10% of the area on the surface within the castle walls. And beyond the castle walls,” he adds, “you see more living areas, the canal, a necropolis where the leading families buried their dead, and ceremonial areas. So, there will be more to come.”

Excavations, he says, could continue for another 30 years.

The entrance to the Mithras temple seen from inside.

Alice Martins for NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Alice Martins for NPR

The entrance to the Mithras temple seen from inside.

Alice Martins for NPR

#Archaeologists #Turkey #identified #massive #structures #Romanera #castle